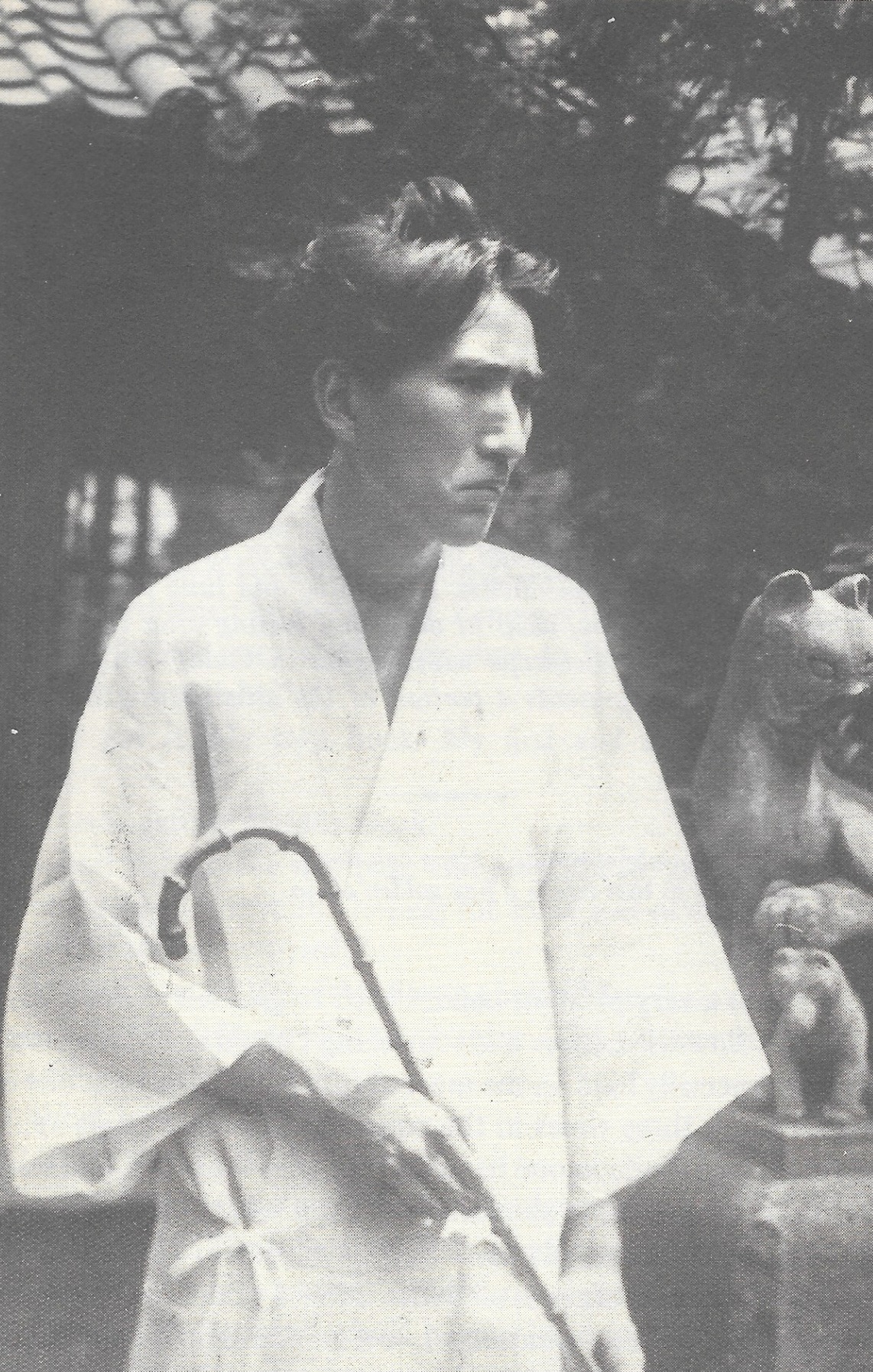

Written by Dazai Osamu and published in April 1937. He began writing it after his hospitalisation in October 1936, and also includes material he scribbled on the walls of his room whilst an in-patient. Translated by Laurie Raye.

Original Text: https://www.aozora.gr.jp/cards/000035/files/271_15084.html

The only thing on my mind is the flower outside the window.

October 13th.

Nothing.

October 14th.

Nothing.

October 15th.

Such profundity.

October 16th.

Nothing.

October 17th.

Nothing.

October 18th.

Jotting something down,

I will peel my fan apart,

Take care, my good friend!

It is time once more to part.

October 19th.

I have been confined to a hospital somewhere in Itabashi since October 13th. After I arrived, all I did was gnash my teeth and cry for three days straight. A cheap little revenge. This place is a loony bin. When the young man in the room next to me opened the sliding door, and saw my yukata hanging there, he muttered something like “This isn’t going to work.” Everyone here is healthier than me. They all have lofty names such as Hoshitake Tarō, Ōkōchi Noboru, etc, and have graduated from universities like Tokyo Imperial or Ritsumeikan. Moreover, they all possess a sense of imperial dignity. Such a shame that each and every one of them was about six inches shorter than me. They are the kind of guys who hit their mothers.

On the fourth day, I went on a campaign tour. Iron bars, a chain link fence, and then after that a heavy door that slams every time it opens or closes, accompanied by the jingle of keys in the lock. The guard on the night shift always pacing, pacing. Within this human warehouse I spoke to all twenty or so patients, launching myself into the task regardless of my health. I met a chubby, fair-skinned, handsome fellow and shook him by the shoulders as hard as I could, shouting ‘You lazy bastard!’ at him. Then to a student who had gone mad from exams, who kept a commercial law textbook by his bedside and read from it like the Hyakunin Isshu, chanting it out loud for as long as he could keep his eyes open, I shouted ‘Stop studying! Exams have been abolished!’ When I told him that, for a brief moment, a look of relief flashed across his face.

There was a twenty-five year-old dressed in serge who, behind his back, was nicknamed Osen-sama. He would, all day long, sit slumped with his legs out to one side facing the wall in the corner of his room, feeling despondent. Even if I suddenly whacked him on the head he would only continue to mutter in a low voice “I’m only twenty-five, let me be. Let me be.” without even attempting to look up at me. So then I chided him to stop sulking and gave him a big bear hug from behind. But, when I had a violent coughing fit, the young man seemed to awake from his stupor and yelled “Let go of me, get lost!” Such was his disgust at possibly contracting lung disease. I was so grateful I burst into tears. “Be strong!” I told him.

Everyone here longed for greener pastures. I returned to my room and wrote a poem called ‘Bring Back the Flowers’ in the style of the emperor’s freestyle verse. I showed it to a young doctor who came to see me on his rounds and we had an earnest conversation about it. I wrote out a line from the poem ‘Afternoon Nap’ that said ‘humans must carry on as humans do’, and we both burst out laughing, our faces red. Five or six million people, five or six million times, have been continuously whispering to each other for sixty or seventy years and taking solace in the words ‘It all depends on your frame of mind.’ From this day forward I won’t let anyone see me cry, not even a single tear. A week in this place will change you, ever so slightly. The cells here are peaceful.

Whether it’s Mankintan from Etchū Toyama, bear bile, Sankōgan or Gokōgan, bite down firmly with your back teeth and endure the bitterness like a man, smile, and sing a little song. Oh my darling, oh my darling sweet pea!

Oh my,

am I just

a wicked

woman?

I know only too well,

it’s all just hot air.

Despite being more beautiful

than a rainbow,

than a mirage…

Am I just wicked?

I haven’t had any visitors for a week. Visits are forbidden, and I’m sleeping in a position like I’ve been beaten up, but it’s because of my fever and not because I’ve been bullied. Everyone here likes me. Mr I, I have only this one ardent wish, all I ask is that you come visit me, since I just can’t settle down. Thank you. How have I become so deeply sentimental? Even if it’s Mr K, Mr Y, the restless Mr H, that idiot Mr Y, dimwitted Zenshirō or Ms Y. I miss you, I miss you so much I’m writhing around in agony. I shall abduct the professor and his wife, Mr and Mrs K, Mr and Mrs F, and we shall all go to Asamushi. I will devise our escape and we will admire the mountain scenery along the way and then, then I will want for nothing.

Oh what would become of this world if it wasn’t for my good self, hm? My fever is now 38 degrees, I beg you, we must outwit it. Though Pushkin died when he was thirty-six, he left behind Onegin. Napoleon gnashed his teeth and said “Impossible is not a word!” Nevertheless, I must carry out my work upon a sacred altar. Come, let us rise up, and demand flowers for one and all!

Get up. Make an effort to look authoritative. I love you, from now until I lose my sight.

A Sunset Song

The cicada realised in the afternoon that it was going to die soon. Ah, it would have been better if I had been happier! I should have fooled around more, with nary a care in the world. Oh, do forgive me, I just wish to fall asleep among the flowers.

Oh, give me back my flowers! (I loved you until I lost my sight.)

The milk, the meadow, the clouds… (Even if the sun should set and leave me completely in the dark, I shall not lament. I have already… lost everything.)

Blank Line

Hitting is all I have left.

A Single Flower

Erase your signatures

Everyone has joined forces

What’s yours

What’s mine

Everyone

Always worrying, worrying

At last, the flower blooms

Keeping everything to yourself is

Horrible

Let’s see now

Let me borrow some

Sure enough

An old man

Doesn’t share anything from his table

It’s alright

The one who walks in front

The white-bearded

old shepherd

I’m certain

Belongs to everyone

Erase your signatures

Everyone

Everyone

Good work

Rendering what little I can

Back-breaking labour

At last, the flower blooms

Oh! Oh!

I forgot to say thank you

With a single voice

Thank you, oh, thank you!

(Did you hear that?)

October 20th.

For the past five or six years there have been a thousand of you, but I have remained alone.

October 21st.

Penance.

October 22nd.

I will never forget the eyes of you who taught me how to die.

October 23rd.

A few insulting words for my wife

Do you have any idea how much I care for you? How much I look after you? How much I carefully defended you? Which one of us was it that needed the money, hm? As long as I had a sprinkling of sparkling Ajinomoto snow on some salted salmon roe or a little bit of nattō served with dried seaweed and mustard then I was content. Which one of us was it who insulted other people? No matter how harshly I was rebuffed in matters of conjugal strife, I never forced things. And which of us was the esteemed paragon who was finally able to win me over? You stupid washerwoman! ‘Wife’ is not a profession. Being a wife is not an office job. Just hold me, depend on me, perhaps my bony arms aren’t comfy enough for you and like a little kitten, entrusting your life to me, you’re not able to fall asleep. What true love looks like, for example, is when the blind girl Miyuki from Diary of the Morning Glory runs heedlessly through the rain, stumbles and falls, yet still chases after her beloved with a manic passion. You alone are my chosen mate. Please, love me with confidence.

But it’d be equally bad if you were like Kazutoyo’s wife. If you were to surreptitiously send me a hundred yen from your secret savings, I wouldn’t know what to do with it. I don’t need a thing. Just answer me with a simple “Yes, dear” and casually say “Of course, dear” in a gentle tone. You’re so ignorant. You know nothing about history. You know nothing of the undulations of the river upon which floats the flower of art. You’re just a little blind mouse gnawing on a fish cake in the corner of the kitchen of a tiny little shack. You weren’t even able to love your one and only husband. You couldn’t even write me a single love letter. You should be ashamed. What is the meaning behind those unspoken gestures of love made by the female body? Ah, do you have any idea how, night after agonising night, I would attempt to gouge out these eyes of mine which saw your flaws unmasked?

Every individual must follow their calling in life. You called me a liar. Speak plainly! You’re actually the one who has deceived me. What kind of lies did I tell exactly, hm? And more importantly, what were the specific consequences of these lies? I want it on record.

You deceived me and threw the one person who entrusted their heart and soul to you into a looney bin. Moreover, I haven’t heard a thing from you in ten whole days, not even a flower or a single bloody pear. Whose wife are you anyway? A samurai’s wife? Give me a break! That said, the small amount of money we received from the T family must be handled with caution. Though I suppose I have no authority here. You have the wife’s privilege in these matters, don’t you?

Everyone knows how it feels to be ashamed. However, there is some truth to the idea of closing your eyes to everything and jumping in regardless. If you can’t do this, and can’t accept my cold-hearted cruelty, then this truly is your crown to bear.

Everyone must follow their calling. Some plant tomatoes in their back gardens, eat fishcakes or devote themselves to the laundry. My calling shatters me to my very core. Even as the flames rise high upon my sleeves I shall oppose the storm and, like a king, I must walk with my head held high, for I was born to bear such a destiny. The bamboo rack upon which hangs the imperial court dress is already dead wood, if you stab at it then its royal covering will collapse and vanish, without uttering even a single cry. Like scattering flowers in the air, release me, I must keep moving forward. My mother’s milk has dried up, she cannot embrace me. Escaping ever upwards, higher and higher, that is my fate. You could never understand this kind of pain, this disconnection.

Get off me, leave me alone!

‘There’s a tennis court here, so play a game with the nurses, you’ll find it relaxing’ a wicked old woman whispered to me. I was grateful for the concern. Just wait and see, tomorrow when I step out into the exercise yard standing there will be a blue demon and a black bear, just like hell. This place is quite possibly the absolute worst madhouse. I too am its prisoner. The guard with a bundle of keys, his hair stinking of pomade, shouts ‘Only one!’ as he shoves me in the back, and I will not be going to the tennis court I longed to see last night.

A cheap little revenge for a cheap little clandestine trick. Everything here is simply nothing more than a bunch of bureaucratic red tape, and this round-nosed Christlike doctor has been chosen as the sacrificial lamb for the sake of these rules and regulations.

‘Look at my temperature chart. I haven’t asked for a single injection since the 20th. Please allow me to have some say in the matter. Will it be okay if I stop taking the injections?’

‘No, your sponsor was most insistent that you continue the course of treatment until full recovery.’

If you keep a goldfish in captivity but don’t take care of it then it won’t live more than a month. Even if it’s a lie, give me my pride, my freedom, and the rolling green meadows!

On top of everything, there isn’t even any value to my name being on record in this place… As for the stuck-up bullshit going on in my room, I simply smiled and left. I shall hand over the torch of honour, which has burned tall, unwavering and pure since the beginning of human history until now, to this stalwart young hero. Be careful, hero, lest you catch the eye of Robespierre.

October 24th.

Nothing.

October 25th.

If you keep a goldfish in captivity but don’t take care of it then it won’t live more than a month. (Part one.)

Just a hastily written note to instil confidence in those younger than me. My writing may be disjointed, but I’m not crazy.

The unreasonable sanctions imposed by society arise from the blind faith the petite bourgeoisie have in the conscience of doctors. It is certainly one of the major contributing factors. I am ashamed of the person I was five years ago who, when reading the final verse of a poem Verlaine wrote whilst he was undergoing treatment in a public hospital – ‘a few insulting words for my doctor’ – couldn’t help but burst out laughing. With a great sense of solemnity, we must gaze into the depths of the doctor’s eyes!

Tricks used by a private madhouse:

- This ward currently has around 15 patients, two thirds of which are normal people. There isn’t a single person here who has stolen or has attempted to steal another’s belongings. They trusted people, and got screwed over by them.

- The doctors here never tell you your discharge date. They don’t give you a straight answer, and endlessly evade the question.

- Without exception they always put newly arrived patients in this one room on the second floor with a good view, the lightbulb is then replaced with a brighter one, and so any accompanying family members feel some peace of mind leaving them there. The very next day, since they don’t have permission from the hospital director to use the second floor, they cast him down below into the same ward as the other fifteen dejected inmates.

- Ah, the gramophone of solace. The first time I heard it I was so deeply grateful I burst into tears. Whenever a new patient is admitted, the first thing the gramophone plays is always Takada Kōkichi.

- The office will never call up your sponsor and ask them to come visit you. Unless you sternly insist upon it, they will never even speak to you. Most of us are released from captivity after two or three years. All we can think about is escaping.

- All attempts at outside communication are prohibited.

- All visitation requests are flatly refused, unless you agree to have a guard present.

- There are many more examples. I’ll jot them down as soon as I can remember them. Surely if I don’t forget them, I will remember them, right?

(On this day, with the promise of being discharged and amidst all this heart-wrenching strife, I thought the sounds of life outside would make my heart burst with anguish. The rumble of thirty or forty cars, the distant roar of an aeroplane, oxcarts and the whirring of bicycle wheels.)

“Let me out!”

“Quiet, you!” came the response, accompanied by a thudding noise. This autumn day comes to a close with a tragic melancholy.

October 26th

If you keep a goldfish in captivity but don’t take care of it then it won’t live more than a month. (Part two.)

Yesterday, no-one came for me like they promised. Thanks for that. So this morning, I picked up my pencil, slowly and deliberately. ‘I love you’, they say. However, those forty-year-old petite bourgeoisie do not understand what it means to love. They are incapable of love. It’s just giving fish food to goldfish. I can say with absolute certainty that they do not love us.

The murmurings of a wife who has lost her husband: “Though a night of suffering may be concealed, when day breaks…” There is nothing more distressing to her than the dawn, and yet this is not her expressing a resentment against sleep. Lying sleepless in the dark, all your sorrows will be made manifest. It is said that when the great Saigō Takamori awoke he would kick off his futon and jump straight up. Likewise I have heard that Kikuchi Kan springs out of bed at about three or four o’clock in the morning and always eats a ridiculously early breakfast. Everyone, without exception, should easily be able to identify that this is how the gentle and tender-hearted soul, who knows more than anyone the harm of sinking into the mire of depression, defends themselves. I have discovered the fatal flaw in Mr Kikuchi’s shield of glory, and I have no regrets. I came to realise that if you decide to give a tribute of even a single cup of milk to the rulers of the earth then, beyond a shadow of a doubt, you will not advance even a single step upon your chosen path.

This is a for-profit hospital, and so they prevent a patient’s discharge through every possible means. It is this noble cause that the president, director, doctors, nurses and guards, each and every one of them, all rigidly adhere to and undertake as their calling in life. Even if you cover your eyes and plug your ears, they will find a gap in your defences, and the numerous evils of this place will creep in from all directions, blowing in through the iron-barred windows like a spring breeze. If anything, it’s rather pleasant. Contrary to that of a preaching pirate, the lecture given by the hospital president – or should I say, the hospital’s main investor – was articulated in a calm and affectionate manner, with a warm and welcoming affectation. The substance of said lecture was, naturally, nothing more than a bottomless swamp of tricks. Moreover, these were tricks that directly took away a person’s life. In the hospital you live without making a sound, without thought, without gossip, it’s as though you’re a corpse – nothing more than a dead dog. One of the guards told me a tale about how someone cooked and ate the flesh off the left arm of a plasterer who fell off his ladder while working, and I completely believe him. Once again I think about that bobbing goldfish.

The phrase ‘human rights’ comes to mind. All of the patients here are no longer human.

There are only two ways in which we can survive and grow. Either we escape, wearing only tabi socks, while being pursued out into the rain, given only one paltry meal, assigned a tiny room, swearing to render what little service we can, lest we sink into the mire of rubbish littering the streets and our short little goldfish lifespans come to an end. Collapsing, we gorge ourselves on the fatty fish food of public opinion until our scales shine bright, and we are showered in praise as insubstantial as paper. A few minutes later, we are completely forgotten about, they sneer at us, and we pass away in cold blood. Or, we hang ourselves, terminating our worthless existence, and in about four or five days what little space we took up in people’s hearts will begin to grow cold. All of it, our entire life, was just a cautionary tale for other people. We don’t even get one night for our own pleasure.

I have never hired a prostitute for the sake of pleasure, even for a single night. Instead I sought out my mother. I sought out breasts. Even though I took baskets of grapes, books, paintings, and other gifts, usually I was just regarded with contempt. If you find what I get up to at night to be questionable, just ask me about it in person. I have never lied about my name and address. You shouldn’t think of it as shameful.

I have never taken a single injection for the sake of pleasure. I used stimulants to lift my spirits when I was both physically and mentally exhausted by the constant crack of the family whip, but you, oh you silly wife of mine, you never had any idea of the suffering I went through. At first I didn’t touch the forbidden fruit, I just pretended to nibble on it, but then I went ahead and ate it and now I’m living with the consequences.

Don’t say behind someone’s back what you can’t say to their face. I followed this principle and for that I was thrown into the looney bin. Without soliciting it, dozens of people, both men and women, would endlessly confess their feelings for me, but then after three months of getting to know me they inevitably start to speak ill of me and spread malicious rumours. Up until that point they had been full of insincere flattery, but the moment they stood to leave and disappeared behind the outhouse I heard them click their tongues followed by the devil’s scornful laughter. Personally, I vanquished this kind of demon.

There’s no word for ‘contempt’ in my dictionary.

Do you know that behind my work there is a strong religious principle? Nay, do you know the extent of my fervour, of its heights?

It would have been better had I turned into a character from my own stories. An idle womaniser.

I avoided the rigidity typical of fencing masters that is demonstrated by certain imposing, elderly writers, such as Satomi Ton, Shimasaki Tōson, and the like, who shout ‘En garde!’ Instead, I practised to obtain the humility of Christ.

By means of a single book, the Holy Bible, the literary history of Japan has been divided into two periods, with a groundbreaking clarity unlike ever before. It took me three years to finish reading all twenty-eight chapters of the Gospel of Matthew. As for Mark, Luke, John… Ah, one of these days I will earn the wings of the Gospel of John!

‘Endure it for a little longer, even if it’s painful. It won’t be all that bad.’ Words said by a forty-year-old. Oh mother, oh brother! We are the only ones who know that our struggles emanate from the unspoken yet sincere affection behind the words ‘Please endure it. It won’t be all that bad.’ Endure this temporary shame, I beg you. Endure it tenfold. Please stay alive for three more years. We can become children of light, all because of my love for you.

When that time comes, you will finally understand. The reality will be that we can embrace our mother, our brother, with our souls laid bare and, experiencing the splendour of sincere love, we can fade away into sleep. Then you will whisper softly to us, ‘We never truly loved.’

‘Well, nevermind. Instead of worrying about others, why not sew up the holes in your own sleeves first?’ If that’s the case then stand up and say what you really mean, why don’t you? Which is: ‘If anyone gets ahead of me, even by a little, then that self-confidence will be crushed and they will wonder; what on Earth could I build, or design, or preserve?’ And then, if they dare to laugh, punch them right in their stupid face!

Do you know just how much study and research a professor has to do? Once a scholar’s gown becomes worn and moth-eaten, then in a flash his influence will inevitably shrink, just as if you were to shave off that distinctive bob from the head priest of the Ōmoto sect.

Stop giving academia your unwarranted respect. Abolish all exams! Play! Rest! We care not for wealth or titles. We only want a rolling green meadow, with no signposts.

Don’t be ashamed of sexual love! The pure embrace of lovers sitting together on a bench by the fountain in a park does not scandalise anyone watching, so why should what happens behind closed doors in the elderly Professor R’s bedroom be considered indecent?

“I want a boyfriend!” “I want a girlfriend!” They want you to feel ashamed, immediately, of the image of a life of indulgence that these words bring to mind. Open your eyes and take a good hard look at the character for ‘love’ that follows the one for ‘sex’!

You must ask, ask, and ask once more, open your mouth and shout out what you desire. It is said that silence is golden, and that good wine needs no bush, but proverbs like these have further accelerated our age into a time of great cultural poverty.

(As you see.)

If you do not let your sorrows be known, then it will be exactly the same as if they didn’t exist, and so with bloody fists you must pound upon the gate, and if you knock five hundred times and still do not get a response, then knock a thousand times, and if after you knock a thousand times it still does not open, then you must climb over the gate. If you let your feet slip and you fall and die, then we will tell your name to a thousand people, and those thousand people will tell a thousand stories about you, and you shall truly have everlasting love and respect. Your face, as beautiful as a flower, will spread to every street across the entire world, to the depths of every winding alleyway, scattering them with hot tears. Die! Even if it’s not much, we will pass down to future generations the indignation you felt towards the evils of this world that caused your death, your portrait will always grace our children’s desks and we will make them promise to recount your story to their children and grandchildren. Ah, in this dark world, I feel a profound shame, alongside the hundreds and thousands of men and women who have had the flower of youth snatched away, for being unable to offer you any meaningful gift other than to cover the world with the grand and splendid centennial celebration, as was promised to you.

October 27th.

If you keep a goldfish in captivity but don’t take care of it then it won’t live more than a month. (Part three.)

Two people are having a conversation about the term ‘real’. One asks:

‘What do they mean by ‘real’? When the lotus blooms, does it or does it not make a popping sound? Is this a grave dilemma concerning what is ‘real’?’

‘No.’

‘The fact of the matter is Napoleon also caught colds, General Nogi also had preferences in the bedroom, and Cleopatra also had to take a shit. Are these things not also what you would call ‘real’?’

They smile but do not answer.

‘Furthermore, Dazai wept and begged for someone to buy his manuscript, Chekov ended up wearing down the threshold of his door until he finally went to give his sales pitch, Gorky was completely under Lenin’s thumb and had a tendency to be an obsequious toady, Proust sent a letter to his publisher kowtowing repeatedly. All of these things are what can be called ‘real’?’

Continuing to smile warily, they nod slightly in assent.

‘You fool! Utilising all of your hard work for others, while struggling and suffering and forgetting about one’s own wife and children, having once been made to carry this standard you now find it difficult to cast aside. Working unceasingly regardless of the rain or wind, one must advance ever higher, and to the ears of the half-dead standard-bearer comes the words ‘Remember your wife!’ You or me, it matters not which one of us, ought to be mindful of setting our sights on the legendary Sasaki at the banks of the Uji river, as the saddle of the proverbial horse is already loose. It is not from the love of fame, but, ever-faithful to the laws of fate, it is a predetermined duty. Crawling up from the depths of the river, even if your vision is blurry, desperately clinging at the gate yet again, clawing your way towards the lives of those whose flower has not yet bloomed. ‘Give up, give up!’ Laughing scornfully at your little drama, they grab your foot and mercilessly drag you down into the mud. Is this what we call ‘real’?’

He straightens up a little and replies: ‘That which is ‘real’ is, just like your good self, not making a big fuss and crying out that a needle is a stick, or even a gatepost, and accurately pointing out that a needle is simply a needle.’

‘What utter nonsense, surely you have studied epistemology? You should also familiarise yourself with dialectics. Although I have every intention of giving a lecture on these topics, today’s youth are still clinging to their felt-covered desks pitted here and there with those immature expressions, ‘real’ this and ‘real’ that, and they are not able to notice the injustice of being stuck in such a state. First brush up on your Introduction to Dialectical Materialism and re-read the first ten pages. It’s fine if you just want to skim over the underlined parts. Let us resume this discussion after you’ve done just that.’

And with that said, they parted ways.

The absolute last resort for knowing what is real are things like records, statistics, scientific results, clinical trials, anatomical features, etc. These days however, the skill required to keep records and statistics has become nothing more than bureaucracy. Science and medicine have already degenerated into the popular science common in women’s magazines, and although the petite bourgeoisie recognise the greatness of certain private physicians they do not comprehend the hardships endured by Noguchi Hideyo. Not to mention how unreliable anatomy can be, that would come as a great surprise to them. Our naturally harsh perception of reality came to an end on the eve of the February 26 incident, now is the time to reimagine our perception of reality in a new light. This is the morning to cry out. This is the moment our flower is about to bloom!

Truth and expression. Surely you must have learnt about the duality of this double-headed ouroboros? Cease this petty rivalry. Now is the morning of our Aufheben. Trust me when I tell you that a lotus does indeed emit a clear ‘pop’ when it opens its petals. For the time being we can call this the ‘Victory of Romanticism’. Stand tall! My dear realist, this is the child born from your thirty years of stoic endurance, your beloved child, a child of light!

Don’t laugh at this child’s blue eyes. They are as if an infant, tender and mild, skin still baby-soft. On the morning of the third day, it’s fine if you want to act like a lion and throw the cub off a cliff. Just don’t forget to spread a futon at the bottom! You can declare them disowned and throw them out like an old silver pipe, saying ‘Hahaha, what a precocious child!’

Pity the intellectual pride! Their final conclusion is that living, dying, and everything in between is a source of pride. Well, just look at the factory workers, take a peek at the state of a farmer’s evening meal! I gradually regained my cheerfulness, but you spent ten thousand yen to graduate from university only to become nothing more than emaciated intellectuals, alone in the dark!

If you are tired, lie down!

If you feel sad, have a bowl of udon and let the game begin.

I only deceived you once, but you deceived me a thousand times. I was called a liar, and you were called wise and worldly. ‘The more outrageous lies you tell, the less you seem like a liar, don’t you think?’

Only a grown man can listen earnestly to the tall tales of a twelve or thirteen year-old girl.

Besides that, I do as I please.

October 28th.

Notes regarding Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time.

It’s rather Verlaine-esque, rather Rimbaud-esque.

The sweet pea wants to imitate the iron-rich sago palm. I think about salarymen riding the iron rails. One man is wearing iron-rimmed glasses repaired with string, a leather satchel with three loose fasteners on his lap. He is hunched over slightly, stroking the two-day old stubble on his chin, absent-mindedly watching the rainy streets outside. He has been beaten and burned, and now conceals that ferrous cruelty within himself… (Entry incomplete)

October 29th.

Crist upon the cross didn’t cast his eyes up to heaven. I’m certain of it. Instead, he looked down bitterly upon the peoples of the earth.

Throw away all the cards in your hand, and laugh!

October 30th.

Rainy day today, awful weather.

October 31st.

(Written on the wall) Napoleon never wanted to conquer the entire world. His only wish was to obtain the trust of a single dandelion.

(Written on the wall) If you keep a goldfish in captivity but don’t take care of it then it won’t live more than a month.

(Written on the wall) To those who come after me: Please make the most out of my death.

November 1st.

I can’t forget Sanetomo.

The white-crested waves of the Izu sea

scatter salt blossoms.

Stirring pampas grass.

Satsuma orchards.

November 2nd.

No-one has come to see me. Bring me some news already!

I’m jumping at shadows. I feel like my body has been ground up and picked clean, right down to the bone.

What I wouldn’t do to be granted a single lettuce leaf.

November 3rd.

Silence is violence. It’s about who controls the reins, and who holds the whip. It has turned out to be a most effective medicine.

November 4th.

‘A single pear blossom.’

I read Satō Haruo’s article ‘The Akutagawa Prize’ in the November edition of Kaizō magazine, and thought it a sloppy piece of work. For that reason, I also thought it was exceptional beyond compare. True love is blind. It is a wild frenzy, it is anger. Furthermore… (Entry incomplete)

Nero remained silent as he gazed out of his bedroom window at the Great Fire of Rome. No trace of an expression crossed his face. He remained silent even in the face of beauty’s wicked wiles. Even when served sweet wine he remained lost in thought.

I think about the silence of the great general as he stood atop the Alps, defeated, beneath plumes of smoke from his burning flags.

A tooth for a tooth. A glass of milk for a glass of milk. (It’s nobody’s fault).

‘Agree with thine adversary quickly, whiles thou art with him in the way; lest haply the adversary deliver thee to the judge, and the judge deliver thee to the officer, and thou be cast into prison. Verily I say unto thee, Thou shalt by no means come out thence, till thou have paid the last farthing.’ (Matthew 5:25–26)

On this stormy night in late autumn I became aware of my complete and utter defeat.

If you laugh at a penny then later that penny will come back to bite you, that’s all there is to it.

My gaze is free from sin.

I have never taken a single injection for the sake of pleasure. All I did was avoid the shouts of ‘En garde!’ from those few imposing fencing masters. ‘Recognise the strength of water over fire. Learn the fluid grace of Christ.’

Other than that, I have nothing else to say.

You must never divulge the secrets of heaven.

(It is the 4th today, the anniversary of my father’s passing.)

November 5th.

When can we meet up? Now, or sooner, or later, or when exactly?

November 6th.

Life in the human realm

Is that a girl’s school? A tennis court. Poplar trees. The setting sun. Santa Maria. (A harmonica.)

‘Tired?’

‘Yeah.’

This is how people live out in the human realm, no doubt about it.

November 7th.

Don’t they say ‘to flog a corpse’? Or should that be ‘to crush a caged bird’?

November 8th.

Deeply overwhelmed

by the fleeting compassion

of human beings,

my eyes welled up with tears.

I suppose I’m getting old.

November 9th.

Outside the window, I see a tattered, late-season butterfly fluttering around over the dark garden soil. Thanks to its exceptional sturdiness, it does not die, but continues to live. Its nature is not ephemeral.

November 10th.

I am to blame. I’m a man who can’t say sorry. My pig-headedness has come back to bite me, that’s all.

Dear teacher.

Dear brother.

Dear friend.

Dear brother-in-law.

My sister.

My wife.

My Doctor.

Even my late father looking down on me from above.

I say to you: I want to go home.

At the birthplace of

a single persimmon tree,

Sadakurō.

Laugh at me all you want – go on, laugh! – It’ll only make me stronger.

November 11th.

If you are keenly aware of your lack of talent and attractiveness then this will turn you into a moody and arrogant man. It is a gift. (My older brother came to visit and we talked for an hour.)

November 12th.

Provisional plan:

- Committed to Musashino Mental Hospital, Itabashi, Tokyo, for one month starting on October 13th 1936. Make a complete recovery from Pavinal addiction. Then,

- Stay in a sanatorium from November 1936 until the end of June 1937 (when I turn twenty-nine years old). I have entrusted the hospital selection to Professor S and the respectable Mr K.

- From July 1937 until the end of October 1938 (thirty years old), I will rent a house in a health resort to recuperate in, for approximately twenty yen, at a place roughly four or five hours away from Tokyo (so that I get as few visitors as possible.) (My thanks to Mr K, who I have heard has kindly offered to lend me his holiday home in Chikura. I wanted to accept this offer, but ultimately, this is also a decision I have entrusted to others.)

After a full year as described above, and adhering to my strict regimen, my left lung should recover completely, and I am confident that I should be able to settle down permanently somewhere in the outskirts of Tokyo. (As one might expect, creative writing is a rigorous endeavour.)

In addition to this, my work while recuperating should consist mostly of reading and, at most, writing two pages a day.

- Karuta of the Morning (Shōwa-era iroha karuta. A ‘Japanese Aesop’s Fables’ style novel.)

- King of the Jews (A biography of Christ.)

Since I already have a plan for the two works listed above, I intend to start writing them slowly. Any other writing will have to wait.

Besides that, next spring, the Wandering Fiction trilogy of full-length novels will be published with an introduction written by Mr S and cover design by Mr I. (This is just a tentative plan, as ephemeral as frost on a blade of bamboo grass.)

Today, at half past one in the afternoon, I was discharged.

‘Love your enemies, and pray for them that persecute you; that ye may be sons of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sendeth rain on the just and the unjust. For if ye love them that love you, what reward have ye? do not even the publicans the same? And if ye salute your brethren only, what do ye more than others? do not even the Gentiles the same? Ye therefore shall be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.’

Human Lost will be included in Retrogression, Yobanashi Café’s first publication, coming out on 19th June 2024, which follows Dazai’s first attempt at the Akutagawa Prize through stories, letters and diary entries. The published version has over 40 footnotes on Human Lost alone with cultural information and references (Eg, where is the October 18th haiku from? Who is the idiot Mr Y and the dimwitted Zenshirō? What on earth is Mankintan? Why did he nickname his friend Osen-sama?), and also includes recently rediscovered and previously lost poetry Dazai wrote in a Bible during his time in Musashino Hospital. So, please consider picking up the book when it comes out! Yobanashi Café couldn’t exist without your support! Please check in with us in June or follow me on ex-Twitter or Mastodon for updates.

That said, there is one really interesting footnote I wanted to include here: According to Dazai in his short memoir Brazen-Faced (鉄面皮) which appears at the beginning of his 1943 novel Minister of the Right Sanetomo, the working title for Human Lost was ‘No Longer Human’ (人間失格, Ningen Shikkaku), which he later used as the title of perhaps his most famous novel. When Dazai writes that ‘all of the patients here are no longer human’, this may be the first instance of him using a prototypical version of this term.